Different from the simple overglaze 'bat' printed wares produced at the Worcester and Caughley factories from the 1750s, Spode's ingenious method involved first the engraving of a design onto a copper plate, second the transfer of the 'print' to the biscuit-fired ware using a cobalt compound and gummed tissue, and finally glazing and a second firing.

At the time it was said that just two 'printers' could produce the same volume of decorated pottery as 100 painters. Importantly, as the technology spread to countless other factories from Staffordshire to Scotland, underglaze transfer printing permitted mass production and - combining utility with ornament - were affordable to a larger proportion of Georgian and Victorian society.

And today it is perfectly possible to eat your Sunday roast off a 150-year-old blue printed meat platter that should cost under £30.

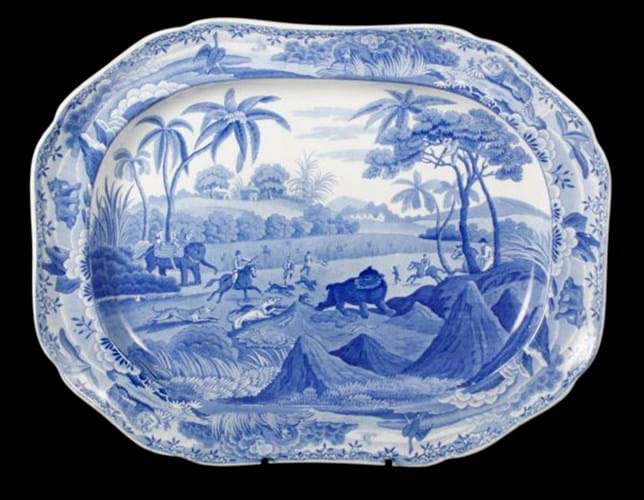

A Spode blue and white Indian sporting series dish from the early 19th century. It has the ‘Dooreahs leading out dogs’ pattern and was offered with a ‘Shooting at the Edge of a Jungle’ pattern strainer. It sold for £1500 at Lyon & Turnbull in February 2019.

What Do People Collect?

The variety of earthenware objects decorated in this manner is vast, from enormous meat dishes to tiny butter boats. The number of factories who made then, including Spode, Minton, Rogers, Clews and Enoch Wood, runs into the hundreds and the number of patterns they produced into the thousands.

At last count, members of the Transferware Collectors' Club had documented more than 9100 different designs.

Early patterns were either copied from or highly influenced by the hand-painted Chinese export porcelain imports that had adorned Britain's finest dining tables since the 17th century. As production advanced and customers' tastes evolved, the variety of patterns grew beyond chinoiserie themes.

The classic Willow design stayed firm in the affections, but landscapes and landmarks closer to home, shipping, sporting pastimes, animals, fruits and flowers provided an apparently endless source of inspiration.

A Spode pearlware shaped rectangular serving dish from the ‘Indian Sporting’ series printed with the ‘Driving a Bear out of Sugar Canes’ pattern, 17in (42cm) wide, c.1815, that sold for £350 at Dreweatts of Donnington Priory on May 23, 2012.

Many of the patterns were copied directly from popular prints and etchings (some collectors try to find examples of the source prints to exhibit alongside the wares) and, in an era largely without patent protection, manufacturers were often happy to copy other makers' designs. Copyright law in the British pottery industry arrived in 1841.

So large is the range that many enthusiasts will choose to narrow their field of vision. Some, for example, will collect by pattern, buying different forms carrying the same design or those from the same series. While dinner wares are most common, a huge variety of everyday ceramic shapes were decorated with underglaze blue and white printing, from toilet bowls to children's toys.

Even when decorated with a common pattern, rare shapes are highly sought after, but it is worth remembering that some of the best known designs developed in the early 19th century showed remarkable longevity. The well-known Abbey pattern rectangular dishes made by George Jones in the early 20th century to promote the breakfast cereal Shredded Wheat carry a backstamp with the date 1790 - not the age of the dishes but the year the pattern was first registered. Likewise Spode's classic Italian design, first introduced in 1816, is still in production today.

Some will collect by shape, choosing to acquire variations of a single form such as feeder cups or chamber pots. Others will collect by factory (for example Spode) or locality (seeking out, for example, only pieces made in Wales or North East England).

The distinctive early pieces, often of a higher quality than later 19th century wares aimed at customers with lower incomes, have particular appeal. The vintage years for blue and white transfer printing were from 1800 to 1835. The fact that most wares from the period have no identifying marks adds to the appeal of the one piece in a hundred that may bear an elusive maker's mark.

Colour can also be important. The high temperature of the glazing oven was the reason why the majority of printed wares are blue - prior to technical advances in the 1820s cobalt was the only colour able to withstand the heat of the oven. By 1822, Spode had developed other colours that could withstand high-temperature firing (green, brown, manganese, grey, and black) with pink and two-colour underglaze printing beginning soon afterwards.

While made in smaller quantities and often harder to find, as a general rule these wares are not as popular as the multitude of different blues, but they do have their followers.

The Market

Blue-printed pottery has a charm lacking in more obviously spectacular British ceramics. The Friends of Blue, a club dedicated to the pursuit of collecting and identifying blue-printed ware, put it thus: "Unlike the finest 18th century porcelain, they put us in touch with a stratum of society that many of us can identify with. Blue-printed wares form a major and important part of our cultural, social and manufacturing heritage."

They are also largely affordable. By the beginning of the 19th century, most potters were churning out masses of blue-printed wares in differing designs. Made for the masses, many pieces from the Victorian era - the typical Willow or Asiastic Pheasant pattern plate among them - are so numerous today as to have little value. As stated above, it is perfectly possible to eat your Sunday roast off a 150-year-old blue printed meat platter that should cost under £30.

A 19th century blue and white transfer printed foot bath, with repeating foliate pattern with carrying handle to either side, unmarked, 20in (50cm) long, that sold for £380 at Mitchells of Cockermouth in March 2010.

Higher values are very much dependent upon form, pattern, date and factory.

Some patterns are particularly desirable on account of their rarity or because their subject matter has wider appeal.

Those pieces with identifiable landmarks, sporting scenes or prize livestock command a premium above those with more generic romantic landscapes or 'sheet' designs.

Much admired for its range of exotic and dramatic scenes, the Indian Sporting series is traditionally cited as the king of all Spode patterns, but four-figure sums can also be commanded by pieces by lesser factories that depict subjects as diverse as polar exploration, cricket matches or the famous Durham Ox.

Size is not always important - some of the most desirable pieces are the small medical wares or the nursery miniatures that occupy specific collecting niches - but as a general rule the largest platters and monumental jugs will bring substantially more than smaller equivalents.

Most buyers are condition sensitive. Although they may display perfectly well, damaged items are very much the poor relation of the exceptional survival.

Blue and white is widely collected across Britain and its export markets but is perhaps most popular in the United States.

The overseas market was key to British potters and a range of wares were made specifically for export, including those printed with patriotic scenes of North American landmarks such as the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, historical events with titles such asLafayette at Washington's Tomb and state coats of arms. These wares (typically in the heavy deep blue print favoured in America at the time) are avidly collected by Americana enthusiasts and command a premium way above more standard blue and white made for the 'home' market.

Here, in the arena many American collectors still term 'old blue historical Staffordshire china', prices begin in the low hundreds, but four-figure dollar prices are common for larger pieces and five-figure sums are occasionally necessary to win the rarest wares at auction.

Further Reading

Spode, Transfer Printed Ware, 1784-1833 by David Drakard and Paul Holdway, ISBN-10: 1851493948.

True Blue: Transfer Printed Earthenware by Gaye Blake Roberts (Editor), ISBN-10: 0953273601.

The Dictionary of Blue and White Printed Pottery 1780-1880, Volumes I & II by A. W. Coysh & R. K. Henrywood, ISBN-10: 1851490930.

Blue & White Pottery: A Collector's Guide by Gillian Neale, ISBN-10: 1840002875.