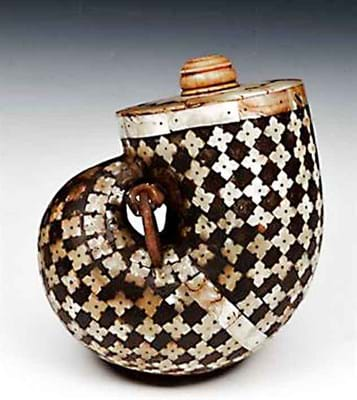

Typically powder flasks were made from some inert, non-sparking material (often copper and brass in the 19th century) and were designed to keep the powder dry in the field.

It was not just a question of keeping the rain out. Black powder is naturally hygroscopic, absorbing moisture from the air, and the flask-makers' main concern was to choose a non-sweating material to counteract this effect. Later flasks were generally fitted with some form of adjustable measure to ensure that the charge was safe and suited to the weapon in use.

Standard 19th century copper flasks are often offered in multiples and few individual examples make more than £50, but exceptional flasks can reach several hundreds. Earlier and more exotic flasks can make four-figure sums.

Examples from recent sales can be viewed by scrolling through the images above right.

Powder-Testers

Before consistency improved in the later 19th century, shooters also had to contend with variable strengths of gunpowder and various types of testing equipment were devised.

Illustrated below are two examples of the flintlock eprouvette. To gauge the potency of a particular powder, the chamber was loaded with a measured charge and fired. The explosive power could then be read off a scale on a sprung-load ratchet wheel.

For those who wish to delve deeper into the world of powder flasks, the bible is still Ray Riling's The Powder Flask Book, first published in 1953. As the publisher's blurb has it: "Where else can you find exactly scaled pictures of 1600 flasks from the earliest gems to reproduction flasks of the nineteenth century? This is not a book that attempts to outshine competitors. It has no competitors."

Though it has been reprinted over the years, even later editions are hard to find under £50 and a good example of the first may cost over £150.