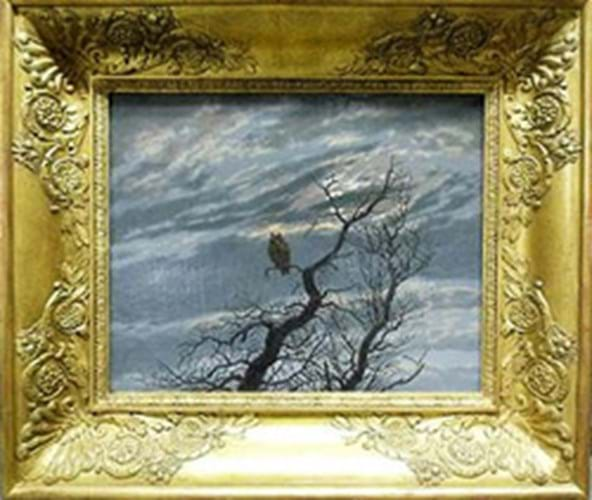

Owl on a Bare Branch, a 10 x 121/2in (25.5 x 31.5cm) oil on canvas, was offered in Cannes on February 10 during one of the weekly ventes courantes (uncatalogued auctions) staged by Azur Enchères, a small firm specialising in estate sales.

The work sold on the phone, against trade underbidding, to Paris dealers Talabardon & Gautier for 350,000 euros (£300,000).

Bertrand Gautier - who was acting on a hunch that it was by Friedrich and was buying for stock - says he only spotted the work, on the French auction website www.interencheres.com, just after noon on the day of the sale. He promptly requested a more detailed image, which the auctioneers emailed him at 1.45pm, just three hours before the sale began.

Gautier says both the subject and its giltwood frame, apparently early 19th century French, made him think the painting was the one seen by the French sculptor David d'Angers (1788-1856) during his visit to Friedrich's Dresden studio in 1834 - described in the sculptor's diary as "a charming painting of a tree with no leaves, with an owl on a branch, and the moon peeping out from behind the branches… a dream-like effect".

A painting with a similar description was mentioned in the inventory drawn up after David d'Angers' death. It is not certain whether he was given it by Friedrich or purchased it during his visit or at a later date. The last trace of this work dates to 1878, when it was in the hands of d'Angers' heirs.

Shortly after the Cannes auction the vendors, who remain anonymous, contacted auctioneer Julien Pichon and partner François Issaly, claiming the sale should be considered invalid by virtue of Article 1110 of the France's Code Civil, which stipulates that "error is a reason to annul a transaction… if it concerns the substance of the item concerned".

Azur Enchères have since refused to release the painting (or, indeed, cash the buyers' cheque).

The wording of Article 1110 is hardly a model of clarity and, in the present case, open to contrasting interpretation.

Insofar as the painting offered in Cannes was correctly, if tersely, described, and accurately dated as 19th century, the auctioneers appear innocent of legal wrong-doing. Such is the personal opinion of Francine Mariani-Ducray, President of France's auction watchdog, the Conseil des Ventes.

Madame Mariani-Ducray also told ATG that, despite the ambiguity it engenders, she felt there was no need for Article 1110 to be redrafted.

However, the vendor's claim here is based not so much on the letter of the law as on a previous, controversial and highly tendentious interpretation of it.

The legal precedent in question concerns the case of the Flight into Egypt offered for auction in Versailles in 1986 as a painting from the "studio of Nicolas Poussin", with an estimate of Fr150,000. It sold for Fr1.6m to Paris dealers Richard and Robert Pardo, who believed it to be a bona fide Poussin painted around 1658.

Their claim received heavyweight backing in 1994 when Louvre boss Pierre Rosenborg agreed with them in his catalogue entry to the major Poussin retrospective at the Grand Palais - prompting the vendor to demand the Versailles sale be annulled and the work returned to her.

In 1998, after a lengthy legal procedure, the Paris Appeal Court overturned an initial judgment and ruled in her favour, claiming that the catalogue description and modest estimate excluded all possibility of the work being a Poussin. The Pardos were forced to return the work, which was eventually acquired by the State for a reported 15m euros, and now hangs in the Beaux-Arts Museum in Lyon.

Although the sale description of the Friedrich was not factually inaccurate (as "studio of Poussin" was deemed to have been), Bertrand Gautier fears that the discrepancy between the estimate and the hammer price could prompt a French court to annul the sale.

Even though nearly four months have elapsed since the sale, and he has yet to see his acquisition, Gautier claims to be "serene" about the situation and hopes it can be amicably resolved. "We are talking to all the parties concerned," he told ATG. "It's a complex situation. One could imagine there might be problems of this sort, given the price."

Some have pointed out that French law appears to penalise dealers from exercising their business to the best of their ability: i.e. by taking risks to back their judgment. They argue that the vendors, despite their ignorance, and the auctioneers, who displayed casualness if not incompetence, are not just legally blameless but stand to benefit from the dealers' knowledge.

Gautier believes that the situation is unjust. "This is embarrassing for everyone, and not good for the market. Part of our role is to be discoverers. But, if you discover something, you can see your acquisition challenged. It's not the auctioneers or the vendors who suffer, it's the buyer."

Just the sort of mess, you might think, which the Conseil des Ventes - that uniquely French body - was designed to avoid, or at least clear up. Yet the Conseil is powerless to intervene unless solicited by one of the interested parties, and there has been no sign yet of any such appeal.

If confirmed as a Friedrich, the owl painting could be worth around ten times what Talabardon & Gautier bid in Cannes. Press speculation in France suggests it could, in due course, be classified as a 'national treasure' and, like the Poussin, acquired by the State - for either the Louvre or the Beaux-Arts museum in Angers.

By Simon Hewitt